Design By Contract Preconditions With Expression Trees

Introduction

Seems like Design by Contract is coming to C# 4.0, replacing the somewhat inadequate Debug.Assert, which is the only thing built into the framework at the moment. However, what are the options for today? In this post, I'll take a look at how to improve current precondition checking techniques using C# 3.0 expression trees.

Design By What?

Design by contract is technique for strengthening the contracts for classes by adding 3 kinds of checks:

Preconditions - What the called method expects from the caller. This is usually various forms of checks on method arguments.

Postconditions - What the called method guarantees upon returning. Often guarantees about the return value.

Invariants - What is guaranteed by the class? That is, the class invariant should be true upon one of the objects methods and again when the method returns.

So why is this even important? One of the merits of Design by Contract are that it can communicate a whole lot about your classes to other people using or reading your code. but they can also be helpful to you, as they allow you to express your intent more clearly and will support the fail-fast principle of defensive programming. The idea here is to produce the error as close to the source as possible.

Lets do a simple example to illustrate why this might be useful, consider the following two classes:

public class Person

{

public Person(string name)

{

Name = name;

}

public string Name { get; set; }

}

public class Account

{

private Person _owner;

public Account(Person owner)

{

_owner = owner;

}

public string GetOwnerName()

{

return _owner.Name;

}

}

It seems that the writer of the Account class is implying that an Account object should have an owner - an instance of Person. However, there's nothing to stop a potential client from doing this:

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var account = new Account(null);

Console.WriteLine(account.GetOwnerName());

}

This fails with a NullReferenceException in line 4 with the following stack trace:

DbCExpressionTrees.exe!DbCExpressionTrees.Account.GetOwnerName() Line 17 C#

DbCExpressionTrees.exe!DbCExpressionTrees.Program.Main(string[] args = {string[0]}) Line 13 + 0xa bytes C#

Now this example is very contrived, since it's blatantly obvious where the bug is. But still, consider if the call to GetOwnerName had been in a completely different layer of the application, maybe even minutes after the Account object had been created. I'm sure you've had your fun with your debugger tracking down errors like this, if you've done any moderate size programs - I know I have.

What we need is a way for the writer of the Account class to communicate a stronger contract on what he's expecting from his client. In an ideal world, this contract would be enforced at compile-time and not allow the program to compile if contracts were broken. A thing I've always wanted for situations like this is being able to specify arguments as non-nullable in C# - that is, give me an object of this type and NOT null - since this makes sense in a lot of situations. Anyway, the only way to get something resembling this today is using Spec#, but this is a research project and still under development. So we will have to settle for runtime checks for starters.

Returning to the fail-fast principle - why is this useful? Consider the following change to the Account constructor:

public Account(Person owner)

{

if(owner == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException("owner");

_owner = owner;

}

Executing the client code from before, our program will now fail when trying to create the invalid Account object with the following stack trace - and a clearly readable exception message (that owner is not allowed to be null):

DbCExpressionTrees.exe!DbCExpressionTrees.Account.Account(DbCExpressionTrees.Person owner = null) Line 13 C#

DbCExpressionTrees.exe!DbCExpressionTrees.Program.Main(string[] args = {string[0]}) Line 12 + 0x17 bytes C#

The benefit here is that this stack trace points directly to the first offense against the "contract". Consider the differences in debugging time on the two examples. Examples like this could also be made for postconditions and invariants.

Expression Trees

Okay, I admit it, I've been itching to play around with Expressions since C# 3.0 was released and especially with all the cool usages in ASP.NET MVC. Furthermore I'll often go to great lengths to avoid "magic strings" in favor of something more type-safe (and refactor-friendly). Also, I happened to stumble upon these two posts by The Wandering Glitchand Søren Skovsbøll where they experiment with Design By Contract and C# 3.0.

Realistically, I preconditions are only viable part of Design by Contract to implement in C# at the moment. While you can probably do crazy postcondition and invariant checking by using exotic things like IL injection or interceptors, I really don't think we'll see any really good solutions until the language provides better support. So I decided to see what I could do on preconditions.

Now, Søren and Andrew (the Glitch) used a general Requires method for defining their preconditions. Søren's looks like this:

public static void Require(this T obj, Expression<Func<bool>> booleanExpression)

{

var compiledPredicate = booleanExpression.Compile();

if (!compiledPredicate())

throw new ContractViolationException(

“Violation of precondition: ”

+ booleanExpression.ToNiceString());

}

When using a lambda wrapped in an expression, we don't get the delegate that we're used to, instead we get something that resembles an abstract syntax tree that represents the expression. This is what enables us to pull various information about the expression. As shown above, the expression can then be compiled into the delegate that we're used to and executed.

However, compiling expressions is not the cheapest operation ever - and I personally believe that it can be beneficial to leave your contracts (if they are runtime) in your production code. Since breaking the contracts in production could lead to undefined behavior (or at least unintended), it would be nice to find the offender easily from the log containing the stack trace. So, since we're most likely going to use preconditions many places, it'd be super nice if they were as fast as possible. But preferably still without the strings.

My preference so far has been to do specialized methods for checking various things. If we have very specific methods for checking stuff the occurs often, we can make assumptions (or requirements) about the format of the lambda expressions and cut out the expression compilation. For more exotic things I'll still use the Requires method as shown above.

The example I'll show here is the same I did in my example earlier namely checking method arguments for null. This is arguably the precondition seen most often - however I've also done others checking arguments for empty strings in much the same way.

My ArgumentNotNull method defined on my static Check class looks like this:

public static void ArgumentNotNull<T>(

Expression<Func<T>> argumentExpression) where T : class

{

var memberExp = argumentExpression.Body as MemberExpression;

if (memberExp == null)

throw new ArgumentException

("Invalid Contract: ArgumentExpression "+

"was not a MemberExpression.");

var constantExpression = memberExp.Expression as ConstantExpression;

if (constantExpression == null)

throw new ArgumentException

("Invalid Contract: ArgumentExpression didn't "+

"contain a ConstantExpression.");

// Argument will be a field on the class.

var fieldInfo = memberExp.Member as FieldInfo;

// The contant expression will contain the object we're

// calling from.

var methodOwner = constantExpression.Value;

// Use the fieldInfo to extract the information directly from the owner

if (fieldInfo != null && fieldInfo.GetValue(methodOwner) == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException(memberExp.Member.Name);

}

The use in the Account class will look like this:

public Account(Person owner)

{

Check.ArgumentNotNull(() => owner);

_owner = owner;

}

and it will throw an exception that looks exactly like the one in my first example, so all the expression / reflection magic was really just to extract the argument name in a type-safe way. The ArgumentNotNull expects only lambda expressions containing a single argument and can thus make assumptions on the generated expression and pull the field value directly from the correct instance without compiling the expression.

But writing these specialized methods takes longer time and the Requires method can capture infinitely more conditions - so is this really worth it performance-wise? I did a small micro-benchmark - note: I've focused on the scenario where there's no error, since it by far the most common occurrence - we don't really care about performance if we're killing the program with an exception.

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var timerArgumentNotNull = new Stopwatch();

var timerRequires = new Stopwatch();

var obj = new object();

timerArgumentNotNull.Start();

for (var i = 0; i < 10000; i++)

TestMethod(obj);

timerArgumentNotNull.Stop();

timerRequires.Start();

for (var i = 0; i < 10000; i++)

TestMethodWithRequire(obj);

timerRequires.Stop();

Console.WriteLine("Argument not null: {0}",

timerArgumentNotNull.ElapsedMilliseconds);

Console.WriteLine("Requires not null: {0}",

timerRequires.ElapsedMilliseconds);

Console.ReadKey();

}

private static void TestMethod(Object obj)

{

Check.ArgumentNotNull(() => obj);

}

private static void TestMethodWithRequire(Object obj)

{

Check.Requires(() => obj != null);

}

And the results were as follows:

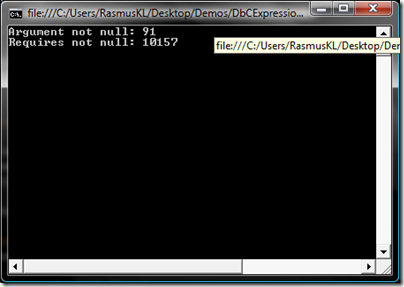

Now the Requires function could probably be optimized (maybe some expression caching), but the difference is quite remarkable.

Conclusion

In this post I've described some of the benefits with Design By Contract and defensive programming and tried to give some insight into using C# 3.0 Expression Trees for avoiding "magic strings" in our precondition checking.